It's Spawning... It's Spawning Time

- scottmorello

- Mar 25, 2017

- 5 min read

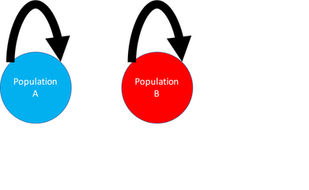

Mussels are, what scientists refer to as, a “sessile” species - meaning they don’t move. But, mussels are also broadcast spawners, meaning at a location, all the male and female mussels go “sploosh” around the same time, and “broadcast” their gametes (sperm and eggs) into the water around them. Depending on the time and place mussels broadcast their gametes, the sperm and eggs fertilize each other, grow into a planktonic larvae, and are carried off by currents until they settle down on a rock to become an adult. The “depending on the time and place” part of that can be very important, since ocean currents can change over time and space, and broadcasting your gametes at one time and place can lead to a very different trajectory for your larvae than broadcasting your gametes at a slightly different time and place. In this respect, understanding when mussels spawn (broadcast their gametes) can be very important to understanding more important processes like population connectivity (i.e., where the babies go and where they come from).

In Downeast Maine (that northeastern area of Maine between Bar Harbor and the Canadian border… although people debate the exact boundaries), mussel harvesting/fishing is still a profitable industry. In fact, it is one of the few remaining viable mussel harvesting industries left in the United States after steady mussel population declines since the 1980s (we get lots of our mussels from Canada now). Thus, understanding the dynamics of mussel populations within this region is very important to keeping the industry alive.

For 3 years during and after my PhD (I started my post-doc before finishing my PhD… it was a busy time for me), I studied these Downeast mussel populations in more detail than most would consider mentally healthy. One element of this research involved monitoring mussel spawning times, which would eventually feed into a model that predicted which currents the mussel larvae would end up in, and where the larvae would ultimately travel to and grow up as adults. Early on in this mussel spawning monitoring, it occurred to my former advisor and I that mussels seemed to be spawning along a gradient from south to north (southern mussels spawning earlier than northern mussels). This was interesting for two reasons:

1) The impetus for mussels to spawn in a location is, as far as we know, very complex - involving a combination of the right temperature, food, tidal cycles, and other cues. So, the likelihood of such a stark gradient is less likely.

2) Mussels much further south of Downeast Maine (even in Massachusetts) seemed to spawn later than many we were monitoring, so documenting the pattern would be important information for New England marine biologists.

We set out to monitor mussel spawning along 75 miles of the Maine coastline. To monitor mussel spawning, you harvest a sample of mussels from a population, dissect out the gonad and weigh it, dissect out the remaining tissue and weight it, and look at the proportion of gonad to somatic (i.e., non-gonad) tissue. The final calculated value is known as the Gonad Index (GI):

Gonad Index = Gonad Tissue Weight / Non-Gonad Tissue Weight

As mussels build up their gonad (i.e., produce their gametes), that gonad index increases because gonad weight increases. The Gonad index drops abruptly when the mussel spawns, because it has released all of the gametes within the gonad into the surrounding water. The period of time when the gonad index significantly drops (tested statistically with ANOVA and Turkey HSD tests) is interpreted as the spawning time for the mussel population.

During our first year of monitoring mussel spawning, we monitored only a few populations, very frequently (weekly) and by sampling lots of mussels (25+). In some mussel populations, however, continuing to harvest at this sample size could be unsustainable to the population… and also, dissecting out mussel gonads is actually a LOT of work. So, after our first year, we decided to run a little bootstrapping simulation resampling our data to see how different sample sizes affected our ability to detect mussel spawning. What you see below are Gonad Indices (min to max Standard Error around the mean) through time for a mussel population we sampled using different sample sizes (color) during the re-sampling analysis. We determined, based on this analysis, that we could decrease sample sizes to 15 individuals per sampling period and safely pickup a spawning signal (significant drop in gonad index).

After that year and analysis, we expanded our sampling effort to monitor more mussel populations across Maine’s Downeast region. After accumulating 3 years of data on ~15 populations, we looked at how spawning time related to a mussel population’s latitude with multiple linear regression. We found a significant relationship, whereby mussels further north spawned later than mussels further south (P<0.05), and that this relationship did not vary among years (P>0.05).

To account for the fact that mussel spawning times might vary just as much locally (within the same mussel bed), we also monitored spawning times at multiple locations within the same mussel bed. We found that all of the mussels within a mussel bed spawned at about the same time. Below, you can see one of the populations we monitored, where each line represents a separate part of the mussel bed, and letters represent gonad index values that are statistically similar (the same letter) or different (different letters) based on a repeated measures ANOVA.

Ok, so we have this gradient in spawning time with mussels in Downeast Maine…. But, why? What is driving the pattern? The pattern in unlikely to be driven by temperature, especially considering mussels in Massachusetts spawn AFTER mussels in Maine in some cases (also, we looked at temperature, and there wasn’t much evidence of a correlation with spawning times). Although we only have a bit of supporting data, it seemed as if algae blooms could drive the gradient in mussel spawning times. For a few months in one year, we monitored Chlorophyll a - a proxy for phytoplankton (planktonic algae) abundance in the water. Phytoplankton is a food for mussel adults, and mussel larvae. Releasing mussel larvae when phytoplankton is high would mean that the larvae have lots of food in the water, and a better chance of survival (i.e., there is a straightforward explanation for how evolution might select for mussels to release larvae when phytoplankton is abundant). When we looked at Chlorophyll a concentration in the water as a function of “days from mussel spawning”, we found that Chlorophyll a peaked right around “0 days from mussel spawning” - so right around when mussels spawned.

All together, our results suggest that mussels spawn along a gradient in Downeast Maine, and that spawning times (and hence the gradient) might be driven by phytoplankton blooms that move up the Downeast Maine coastline in the spring and summer. Obviously, the phytoplankton hypothesis needs more research, since data is limited, and Chlorophyl a could be correlated with a bunch of other spawning cues… but hey - it’s a start. And also, now you know when mussels’ go “sploosh” in Maine… so there’s that.

Comments